Getting into the spirit of no-low – A closer look at how no-low ‘spirits’ are made, plus their legal requirements

No- and low-alcohol ‘spirits’ are a new, fast-growing category of beverages which are increasingly gaining traction among European consumers. We take a look at the category and review the different production methods along with the legislation or guidance on labelling.

No- and low-alcohol ‘spirits’ have burgeoned over the past few years, morphing into a force to be reckoned with for the beverage industry. Multiple product launches in recent years illustrate the ability of Europe’s spirits industry to ramp up innovation and fulfil consumer demand by broadening the choice of products on offer.

Alcohol-free (generally under 0.5% ABV – alcohol by volume) and low- alcohol ‘spirits’ (< 1.2 % ABV) are not (yet) legally defined by specific EU legislation. However, as a general rule of thumb, they contain either no alcohol, less than 1.2% ABV or can creep up into the double digits.

Definitions of no-low ‘spirits’ can vary considerably from one country to another and use of the word ‘spirit’ in itself can be confusing for consumers. The temptation to compare them with their full-strength counterparts does not necessarily work to their advantage, which is why some producers tend to steer clear of conventional rules and norms for labelling and presentation.

No-low alcohol, a growing category

The IWSR forecasts that “no- and low-alcohol volume will grow by +8% CAGR (Compound Annual Growth Rate) between 2021 and 2025, compared to regular alcohol volume growth of +0.7% CAGR over the same period. Beer/cider is the largest no/low category (at 75% volume share), with no-alcohol beer projected to drive growth at more than +11% CAGR over the study’s 2021-2025 forecast period. Alcohol-free RTDs and spirits are both expected to post about +14% CAGR volume growth. The wine category is the exception, as the taste of low-alcohol wine is perceived by many consumers to be superior to that of no-alcohol wine. Low-alcohol wine is expected to grow almost +20% CAGR 2021-2025, vs. no-alcohol wine projected at +9% CAGR”.

Moderation is the most common driver of no/low alcohol beverage consumption, with significant cross-over between no/low and full-strength alcohol consumers. According to new IWSR research, 43% of adults across the focus markets who have purchased no- and low-alcohol beverages say they are substituting full-strength alcohol on certain occasions, rather than abstaining from alcohol altogether.

How are non-alcoholic spirits made?

Here we list five different techniques that can produce low or no-alcohol spirits.

- Distillation

Distillation is not only used to produce spirits. The dictionary definition describes it as a purification process by boiling followed by condensation of the steam in another receptacle.

Water is regularly distilled. Consequently, use of the term ‘distilled’ to describe a non-alcoholic or low-alcohol ‘spirit’ is possible, provided the product’s manufacturing process involves distillation.

1.1 Distillation of alcohol or a spirit

The most obvious choice for producing no-low beverages is to distil a spirit such as gin, whisky, tequila or rum. Distillation’s normal purpose is to concentrate alcohol and aroma. However, the process can be reversed using distillation equipment fitted with a separation column where the alcohol is stripped and the aromas are separated from the mixture through fractional distillation. As alcohol evaporates easily, it can be removed during distillation while at the same time preserving aromas, which are consequently found in the aqueous phase. Some aromas, though – for instance the most volatile ones – are lost during the redistillation process. That’s because they bind to varying degrees with the alcohol or water molecules depending on their affinity with particular components of the mixture and have very different volatilities (they can be lighter or heavier).

Reduced-pressure distillation is a better option for preserving the integrity of the aromas and is mostly used to produce alcohol-free wines.

Distilling a spirit is a worthwhile option when reproducing some of the aromatic notes is challenging without the alcohol base. This is true of aromas specific to mature spirits.

Over the past fifteen years, Belgian company Univers Drinks has specialised in producing alcohol-free drinks, running the gamut from sparkling and still ‘wines’ to non-alcoholic cocktails and spirits. One of the leading players in the European market, it sells three products labelled ‘Pure Zero’ which are redistilled gin, Amaretto and whisky.

[/fusion_text][fusion_text columns=”” column_min_width=”” column_spacing=”” rule_style=”default” rule_size=”” rule_color=”” content_alignment_medium=”” content_alignment_small=”” content_alignment=”” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” sticky_display=”normal,sticky” class=”” id=”” font_size=”” fusion_font_family_text_font=”” fusion_font_variant_text_font=”” line_height=”” letter_spacing=”” text_color=”” animation_type=”” animation_direction=”left” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_offset=””]

“Distilling a spirit is a worthwhile option when reproducing some of the aromatic notes is challenging without the alcohol base. This is true of aromas specific to mature spirits.”

[/fusion_text][fusion_images picture_size=”auto” hover_type=”none” autoplay=”no” columns=”3″ column_spacing=”13″ scroll_items=”” show_nav=”yes” mouse_scroll=”no” border=”yes” lightbox=”no” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” class=”” id=””][fusion_image image=”https://spiritsselection.com/app/uploads/PVREZERO_AlternativeToStrawberry_70cl_ZIP.jpg” image_id=”11862″ link=”” linktarget=”_self” alt=”” /][fusion_image image=”https://spiritsselection.com/app/uploads/PVREZERO_AlternativeToSpirit-ZIP.jpg” image_id=”11861″ link=”” linktarget=”_self” alt=”” /][fusion_image image=”https://spiritsselection.com/app/uploads/PVREZERO-GIN.jpg” image_id=”11860″ link=”” linktarget=”_self” alt=”” /][/fusion_images][fusion_text columns=”” column_min_width=”” column_spacing=”” rule_style=”default” rule_size=”” rule_color=”” content_alignment_medium=”” content_alignment_small=”” content_alignment=”” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” sticky_display=”normal,sticky” class=”” id=”” font_size=”” fusion_font_family_text_font=”” fusion_font_variant_text_font=”” line_height=”” letter_spacing=”” text_color=”” animation_type=”” animation_direction=”left” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_offset=””]

1.2 Distilling water and producing a hydrolate

In this instance, a number of ingredients are added to water before the mixture is heated in distillation equipment such as a ‘florentine flask’, which concentrates aromas. The technique is similar to the one used for producing essential oils – such as extracting lavender or geranium oil – for perfumers.

To avoid any charred flavours – water evaporates at 100°C – reduced-pressure distillation can also be used. Boiling temperature is thus lowered to 40 to 50°C.

Despite this, alcohol-free brand Djin uses a tried-and-tested technique of heating with high-pressure distillation (120°C). The craft manufacturer produces some alcohol-free organic products labelled ‘Esprit de plantes sans alcool’.

Bax Botanics uses traditional copper alembic stills, similar to those used to produce essential oils and hydrosols.

When this technique is used, the end product generally contains no alcohol at all and can be marketed as a non-alcoholic drink.

“In the production of an hydrolate, the ingredients are added to water before the mixture is heated in distillation equipment such as a ‘florentine flask’, which concentrates aromas.”

- Infusion

This involves combining botanicals (plant or fruit extracts for instance) and so-called natural aromas with water. The idea is to soak the ingredients though the aromas or botanicals must be highly concentrated. In this instance, there is no distillation. Occasionally, the base can be a tea infusion which lends tannin structure to the end product. Some producers add sugar using a sweeter substance than sucrose, namely Stevia, a plant containing natural sweeteners, which imparts structure and viscosity. Usually, pasteurisation or flash-pasteurisation ends the production process due to the fact that botanicals always contain some sugars that can develop fungus. Without pasteurisation, the products do not keep for long after opening.

- Reverse osmosis

This process separates alcohol from other residual compounds using a partially permeable membrane where pressure higher than the osmotic pressure of the spirit is applied, resulting in a permeate. To achieve this, micro-filtration by osmosis is used with a membrane contactor. The technique is mainly used by brewers and winegrowers, for example in very hot years when alcohol levels in wine are too high and there is a need to reduce ABV.

However, the technique only has a partial ability to de-alcoholise and needs to be used in conjunction with distillation for greater efficacy.

- Spinning Cone Column (SCC)

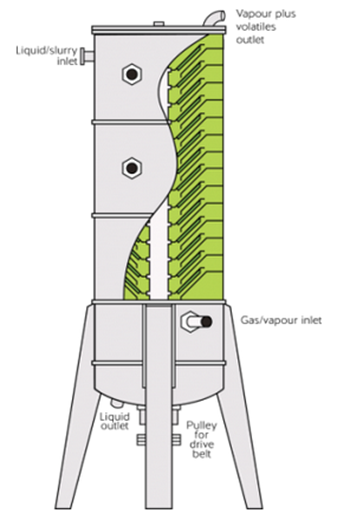

This technology was developed by Australian company Flavourtech and follows the principle of vacuum evaporation or low temperature distillation. It separates the alcohol from the most volatile compounds such as aromas.

It occurs in two stages:

- The first stage involves running the liquid from which the aromas are to be extracted over a column equipped with spinning cones. Through centrifugal force, the liquid forms very thin layers on the surface of the cones and drops down from cone to cone. Simultaneously, steam is pumped from below. Contact between the steam and the thin layer of product allows the aromas to be collected in the end product. The steam packed with aromas is then condensed.

- The second stage involves de-alcoholising the liquid using vacuum distillation.

The aromas are then reintroduced into the de-alcoholised product.

This is a far more gentle process compared to standard extraction techniques, enabling aromas and flavours to be more efficiently captured.

@credit – Flavourtech®

A more detailed look at the SCC – Flavourtech®

The feed material, from which the volatile compounds are to be separated, is fed into the top of the column. This material flows as a thin film (approximately 1mm film thickness) down the upper surface of the first stationary cone. It then drains through the outlet of the stationary cone on to the base of the spinning cone immediately below. Centrifugal force, generated by the rotation of the cone, causes the liquid to flow upwards and outwards across the upper surface of the spinning cone. The liquid works its way, cone by cone, from top to bottom of the column. At the same time as liquid is flowing down the column, stripping steam (vapour) is introduced into the base of the column. The vapour flows upwards, across the surfaces of the volatile-rich liquid films, separating (or stripping) the volatile compounds from the liquid. The temperature and flow rate of the stripping steam can be controlled. The vapour, which is now steam mixed with the volatiles stripped from the product, flows out of the top of the column and passes through a condensing system.

Significant takeaways from all of these techniques

The desired outcome is to preserve aromas without distorting them. Distillation and osmosis are processes which tend to break down the product and its aromatic structure. From this perspective, infusion is a gentler technique.

Whatever the chosen method, producing these products successfully is a challenge. The absence of alcohol translates to a lack of texture and balance on the palate. Introducing sugar can compensate for this lack of structure, provided it is used in limited quantities. Nevertheless, reproducing some aromatics is difficult and the ultimate choice of technique depends on the desired product style.

Chris Bax, the founder of Bax Botanics says:” It is significantly harder to extract flavour from botanicals using water rather than alcohol. There are many “make your own gin” experiences where complete beginners can create a palatable gin. I challenge anyone to try and recreate these results with alcohol free distillations. It is significantly harder, which is why some manufacturers of alcohol free spirits use artificial flavourings and not traditional distillation”.

“It is significantly harder to extract flavour from botanicals using water rather than alcohol”

Exposure of all these products to air is also an issue that requires careful attention because alcohol is no longer there to preserve them. Any open bottles should therefore be drunk rapidly and stored in the fridge. Also, a sell-by date should be stated on the labelling.

“But not every product has (likely) a short shelf life” comments Nicolas Medicamento from Doctor Cocktail Ltd. “Our products are incredibly stable. They do not require pasteurisation and will store at ambient temperature after opening (tested to 6 months). This is because of the distillation process, clean ingredient deck and sterile filling of bottles”, adds Chris Bax.

Currently, most alcohol-free spirits are produced by prominent spirits groups – from a volume perspective – and a clutch of specialist manufacturers that provide sourcing for most of the brands. These companies invest in research to improve extraction of aromatic compounds and develop new products.

“In my opinion, a lot of these products are crowd-pleasers”, says Romuald Vincent, founder of Djin. “Few products are genuinely craft. However, quality improves year-on-year and demand is booming, especially in some markets like the UK”.

Spirits enthusiasts may not understand or buy into these products. “To enjoy them, you have to have a change of mindset. Trying to compare them with spirits is not the right approach. It’s like comparing apples and oranges”, adds Vincent. For Arnaud Jacquemin – Univers Drinks, “the most important thing is that the product has to be enjoyable, offer certain similarities with the spirit it is made from in the case of redistilled spirits, offer complexity and length on the palate”.

The primary usage for the products is in long drinks, where tonic water or other soft drinks are added. Drinking them neat, as ‘shots’, is challenging and it is preferable to follow the recommendations of the producer who can advise on which type or brand of tonic water or soft drink to use.

Are price points justified?

Consumers may wonder why these products are fairly expensive, and quite rightly so. Retail prices range from 25 to 40 euros. Producers who redistill spirits will tell you that you have to produce the spirit and then redistill it, making the process extremely costly. Despite the price points, though, sales are growing apace.

As Chris Bax pointed out, it is significantly harder to extract flavour from botanicals using water rather than alcohol. “It requires more raw ingredients and more energy to produce an alcohol free spirit, and it takes much more time to create the same volume of alcohol free spirit than it does to create alcohol based spirits using our traditional process”, he adds. “Our process and attention to detail makes us comparable to an artisan spirit product selling at upwards of £40.00, but at half the price. I think that UK alcohol duty on a bottle of gin is around £11.50 (over 40% ABV) so prices are comparable when we examine like for like quality. An alcoholic drinks value is based on its quality and the skill of its maker rather than its ABV. Shouldn’t the value of an alcohol free distillation be based on this as well?”

Nicolas Medicamento feels however that this is making it really difficult to have an appropriate Gross Profit on cocktails with these products, and this issue is massively slowing down the “success” of the category.

Arnaud Michaud has a different opinion on the issue and feels that the prices are not justified. “Consumers know how to put things into perspective and we believe that this is not sustainable in the long term. The consumer should not have to pay as much for a non-alcoholic spirit as for a gin, for example. Pure Zero’s strategy is to market products to consumers at €9.90, which reflects the true price of the product. We are seeing that in supermarkets, a lot of alcohol-free spirits don’t have any depletions. There needs to be a happy medium”.

It may be that the market will segment into different quality price points like every other craft beverage. Some consumers will be content with basic, mass-produced products. Others will want to search out higher quality, or more interesting brands.

“It may be that the market will segment into different quality price points like every other craft beverage”

Bax comments: “It happened with craft beer and with gin. In these sectors consumers now understand and accept that there is a wide price range and that they are free to make a choice. The same will happen with alcohol free spirits. The market is a little confused at the moment and I think that it makes life difficult for the consumer, but I am completely convinced that with experience and education, products will settle into their different price points.”

Straying off the legal path

As mentioned previously, no- and low-alcohol ‘spirits’ (1.2% ABV) are not (yet) legally defined by EU law, neither are self- explanatory descriptive names widely agreed. Therefore, on-label information must clearly inform consumers about what the product is, or is not.

No use of/reference to protected spirit drinks categories and Geographical Indications (GIs) is

permitted on labelling. So low-alcohol gin, rum, whisky, Scotch whisky and cognac, for instance, are not acceptable. The ban also applies where legal names or geographical indications are used in conjunction with words or phrases such as ‘like’, ‘type’, ‘style’, ‘made’, ‘flavour” or any other similar terms.

A cursory glance the marketplace shows that many no-low alcoholic beverages do not comply with these legal requirements.

Want to know more about the legal requirements of no-low ‘spirits’? Click here for more information.

Thierry Heins

@credit picture cover page – Ulric Nijs