The history of wine and distillation in Veneto

Veneto and its agricultural heritage, particularly its vineyards, are inextricably linked.

The area set between the Dolomites, Lake Garda and the Venetian Lagoon owes its present-day configuration to a number of factors. One of them is its geological structure, with abundant water resources criss-crossed by valleys that provided access to trade routes. The region is home to significant waterways and access to the valleys of northern Europe, which are pivotal to trade. The Via Postumia linking Genoa to Aquileia and onto Slovenia provided the East-West route. The Via Annia and Via Claudia Augusta, connecting Venise to the Danube region via the Alpine passes, established the North-South route.

The Romans produced vast amounts of wine here, which they often blended with those of Istria and the Marche before sending them off to their legions. Transporting wine in amphora began to transition to casks, and Strabo referred to Veneto with its “barrels as big as houses”.

Venice and La Serenissima’s rise to power transformed Veneto into a powerhouse of wheat production but it also brought improvements to other crops, fruit growing and wine, extending the trade routes thanks to an impressive flotilla.

The busy merchants and travellers to Venice led to the spread of inns and bistros whose numbers increased during the carnival. Galileo Galilei dedicated a ‘Dialogue concerning the two chief world systems’ to his Venetian friend Gianfrancesco Sagredo. Their encounters were made all the more memorable by the glasses filled with “cold and fizzy wine”, probably referring to a drink akin to Prosecco.

The Venetians were also renowned for importing wines and blending them according to markets and prices. This custom, known as the ‘Venetian method’ – or blending wines from different vintages – was unheard-of in Europe and aimed to standardise a product that could be extremely variable in terms of provenance and winemaking techniques. From the 17th century, Venice’s sway over the European trade markets and quality wines began to gradually wane. This was due to the fact that it underestimated the impact of the beverage revolution with increased consumption of coffee and tea, and subsequently the development of the Bordeaux wine industry and control over trade exerted by England and Holland after the Peace of Westphalia. New models began to emerge, focusing on sweet wines with high alcohol content, and the ‘Venetian method’ was superseded by the ‘English method’ where wines were fortified using distillates. Venice lost the market for sweet wine in the markets of Northern Europe specifically because it underestimated the role that the ‘spirit of wine’ would play in creating fortified wines. Venice also made another mistake by reacting to fortified wines – particularly Port – by trying to imitate absinthe, which was very popular on French tables at the time, by producing vermouth. This innovation was poorly perceived by consumers of the time who viewed aromatised wine as fake.

Despite its decline, however, Venice took some decisive initiatives regarding the development of winemaking. In 1769, it encouraged the founding of the Academy of Agriculture in Treviso, followed the next year by a similar Academy in Conegliano. In 1876, the school of oenology was founded and, in 1923, the institute for experimental viticulture. Conegliano would become an important centre for winegrowing and winemaking.

Distillation spread across Veneto between the 13th and 14th centuries. As mentioned before, Venice was a sizeable market for wine and distillates, whose usage was still more medicinal than hedonistic, were also exported to the Orient and Northern Europe as a remedy for several diseases and ailments such as the plague and gout. One of the first treatise, ‘De Conficienda Aqua Vitae’, was written in the 15th century by Paduan doctor Michele Savonarola (1384 – 1462), the grandfather of the famous Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola. Grape pomace is not explicitly mentioned but it was probably already being used in the 14th century. Considering that distillates were generally consumed by the lower classes, the waste from wine production may have provided a viable way of producing cheap grappa. Distillation companies began to flourish in Veneto and nowadays it is one of the most highly significant regions in Italy for producing grappa, brandy, fruit distillates and aperitif-style drinks across-the-board.

Davide Terziotti

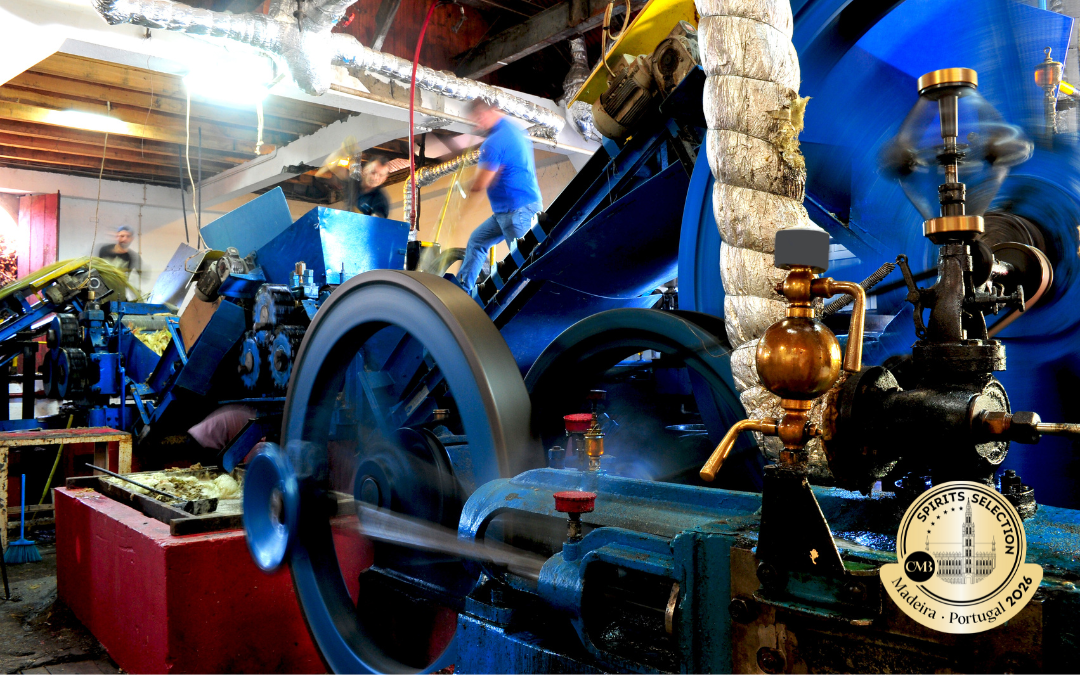

Credit photo cover page – Distilleria Brunello – Caldaiette