Shochu and Awamori – The well kept secret of Japan!

If Western consumers are a little more familiar with Japanese sake, it is not the same for their distilled cousins, Schochu and Awamori. And for good reason, barely 0.5% of the national production is exported. An overview of these categories, so diverse and which would delight more than one palate on the old continent.

Shochu and awamori have been produced for nearly 600 years in Japan, when the distillation technology from Mesopotamia was introduced in the archipelago. Today, 271 distilleries, mainly located in the south of Japan on the islands of Kyushu and Okinawa (for awamori), share the production of 380 million liters. Shochu and awamori are mostly bottled at 25% ABV, but there are variants at degrees up to 43%.

Schochu, Awamori, what are they?

Shochu should not be confused with Korean soju, vodka or Chinese baijiu.

It is a spirit obtained by distillation in pot still (discontinuous distillation – one distillation only) or in column (continuous distillation) from a large list of ingredients: sweet potato, barley, rice, carrot, buckwheat, brown sugar cane, etc. These different ingredients, as well as fermentation temperatures, distillation styles, filtration options and aging techniques allow for a wide variety of products.

The main ingredient of shochu is often dictated by local crops, although sweet potato and barley share 87% of the volumes produced. For awamori, only rice is used.

There are four geographical indications (GI) for shochu in Japan. In each case, the designation is linked to a local crop: for example, barley on the island of Iki (GI Iki), rice in Kyushu (GI Kuma), or sweet potato (GI Satsuma).

Koji, an essential ingredient

To transform the starch contained in these natural materials into fermentable sugars, the Japanese cultivate a “leaven”, called Koji, from rice heated by steam and sown with a domestic mold known as “Aspergillus oryzae”. The seeded rice is left to rest for an indefinite period of time before being put in contact with the chosen ingredient (rice, sweet potato, barley…). It is this “koji”, a key ingredient in Japanese cuisine, that serves as an enzymatic medium to saccharify the starch and release the sugars, but also the glutamate known as umami. In the West, it is the malting process that plays this role, at least for cereals.

For awamori, all the rice used is processed by the koji at once; for the various types of shochu, the koji is processed in two stages: first, a concentrated culture is grown in a small volume of the ingredient to be fermented; it is then added to the rest of the batch. In the case of sweet potato or barley shochu, for example, the koji is first grown to facilitate its reproduction, and then propagated in a much larger quantity of barley or sweet potato.

The koji used are not all the same. Black koji (a variety of rice native to the Okinawa islands) is used exclusively for awamori, while yellow or white varieties are used for shochu.

Yamato Zakura Koji Buta with Rice Koji – After two days in a koji tray, this rice is fully inoculated and ready for the starter fermentation.

Fermentation and brewing

Once the initial koji crop is produced and its propagation is ensured to the whole mash (koji + rice, barley + rice, sweet potato + rice….), the starch is transformed into simple fermentable sugars and the yeasts take over to transform them into alcohol. The transformation of starch into sugars can continue while the yeasts have already accomplished their work on the sugars already released, which allows the production of alcohol in much higher concentrations (around 20%) than in the production of whisky, rum or wine.

There is thus a certain similarity in the manufacturing process of Japanese shochu and Chinese baijiu, namely the preliminary production of a particular medium allowing the transformation of starch into sugars, although for the latter, the “qu” (by analogy with the koji), is used beyond the simple saccharification. Please refer to our article on the manufacturing process of baijiu. https://spiritsselection.com/en/the-spirit-of-china-forever/

Amakusa Clay Fermentation Pots in Floor – Small shochu and awamori distilleries often use clay pots for fermentation. They’re sunk up to their shoulders in the distillery floor to help with temperature regulation.

Nishiyoshida Red Sweet Potatoes – Sweet potatoes must be inspected by hand, one by one. The ends are trimmed and bruises are carved out.

Distillation

The most popular traditional shochu, “honkaku shochu” (“authentic shochu”) is, like awamori, distilled only once in pot stills. The one-pass distillation is self-sufficient since the very special fermentation of shochu allows to reach already naturally high degrees. The Japanese attach great importance to the preservation of the primary aromas. It is to be noted that some stills work at low pressure, which allows to accentuate the fruity character. Finally, shochu and awamori are often consumed during the meal, hence the alcohol levels are often lower than for the majority of Western spirits.

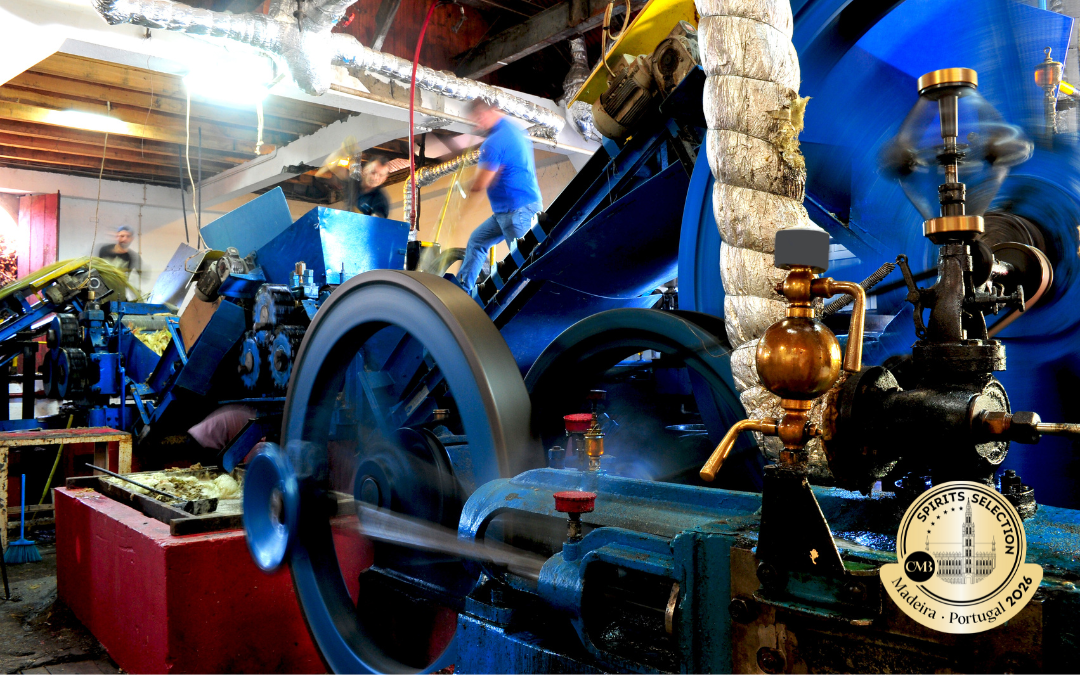

Nevertheless, there are shochus produced in a more industrial way in column stills.

Chiran Jozo Pot Still – The pot stills used to make Honkaku Shochu and Ryukyu Awamori are made from steel.

Storage and aging

The shochu must rest a few months in stainless steel tanks or jars to soften and round off its taste. Some producers are experimenting with aging in barrels, but with an age limit of 5 years. A law determines the color of shochu and Japan wants to protect the identity of its production. A prolonged ageing in barrels would give tastes too similar to those of our western spirits. Nevertheless, we find awamori aged for several years in neutral earthenware jars called “Kusu”.

Chuko Clay Pot Aging – This awamori distillery ages some of its distillate in unglazed clay pots.

How are schochu and awamori consumed?

They can be drunk neat, diluted 50/50 with sparkling water, cold or hot water, or with ice cubes. A multitude of food and shochu pairings are possible due to the wide variety of aromatic profiles.

Let’s taste some samples

Rice Shochu – KAWABE (Kumamoto) – 25% ABV

Very fruity and floral on the nose. The mouth is harmonious, supple, soft, one finds well the taste of rice.

Awamori – HARUSAME – 43% ABV

This awamori has been aged for 5 years in earthenware jars.

We find pronounced umami flavors, accompanied by a nice fruitiness, notes of steamed rice and mushrooms. Very smooth in the mouth.

Barley Shochu – YAMANOMORI – 25% ABV

The cereal comes out immediately, with smoky scents.

Sweet Potato – KURO KIRISHIMA – 25% ABV

The nose develops on notes of lemon, pumpkin, sweet potato

Acidity in mouth, with a persistent bitterness. It is a shochu which is drunk rather young.

Sweet Potato – DAIYAME – 25% ABV

Very different from the previous one, marked by notes of lychee, which come from the use of very ripe sweet potato. To dilute with soda or ice, to give a very refreshing drink.

Brown Sugar Shochu – BENISANGO – 40% ABV

We are in the world of rum. Produced from brown sugar cane. To be served with a dessert.

Christopher Pellegrini – Founder,Honkaku Spirits LLC – Thierry Heins – Director Spirits Selection