Logging for barrels in the land of Uncle Sam – Part 1

Oaks are logged in various parts of the world to produce barrels, particularly in Europe and the United States. But there are fundamental differences in the way forests are managed and this can have long-term implications for the quality of the materials and sustainability of the industry.

In the United States, white oak – aka Quercus alba – is used to supply the sizeable bourbon cask industry which in turn supplies the huge used barrel market that other spirits categories have long tapped into. But how are white oak forests managed and what are the species’ characteristics? How can the growing needs of the bourbon industry be met? And is the barrel market under pressure? We shed some light on the transformation of white American oak into barrels that will house most mature spirits around the world.

In two previous articles which you can find on our website – The pivotal role of stave mills in the production of barrels part 1 and part 2 -, we focused on describing two species of oak logged in Europe to produce barrels, namely pedunculate oak or Quercus rober, and sessile oak or Quercus petrae. Depending on the size of the grain, the barrels are either destined to be used for wine production – for the fine-grain versions – or spirits production for the coarser grain, although nowadays, fine-grain wood can also be factored into the spirits equation. Both species grow slowly and it takes over 150 years to obtain quality logs designed for producing barrels.

In the United States, the oak used to produce barrels primarily destined for maturing spirits – mostly bourbon – but also wines, is white oak or Quercus alba. White oak can produce all types of grain, from extremely fine to coarse. It grows quicker than its European counterparts and can be logged after 80 years.

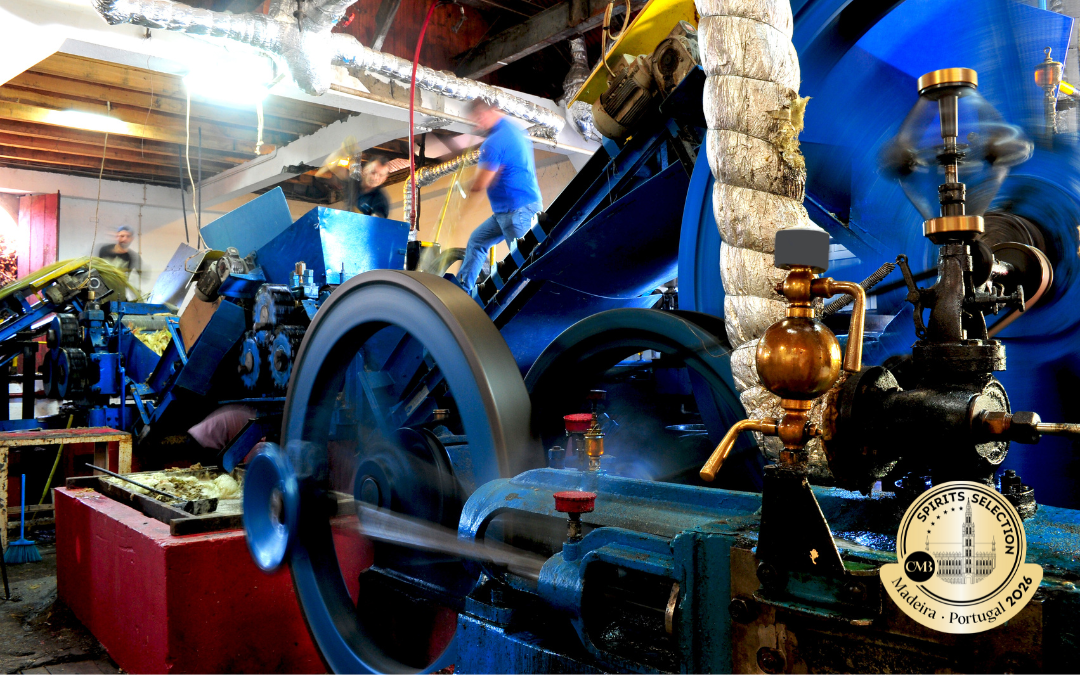

To gain a better understanding of the American oak industry, we travelled to Kentucky, the home of bourbon, at the invitation of the American group, Independent Stave Company. This family-run group is one of the largest producers of stave wood and barrels in the world. Brad Boswell, the family’s fourth-generation representative, runs the group which owns 9 stave mills in the USA (soon 11) and one in France’s Vosges region. The company also owns 4 cooperages in the USA, two in France, one in Ireland, one in Chile and one in Australia.

European and American oak – different species and forestry management

To meet the technical requirements of producers and maximise yields, barrel manufacturers primarily look for logs – i.e. the trunks of the felled trees whose branches have been removed – that are straight with the least amount of knots.

In France, oak forests have been managed for several centuries to guarantee production of quality logs, originally to build boats and buildings but nowadays to produce parquet flooring and stave wood. Oak stands are managed in such a way that competition is maintained in the lower at the lower levels through fairly dense stands, forcing the trees to grow tall in search of light. The oaks thus develop fewer side branches which cause the formation of knots and lower the quality of the logs. This is an essential criterion for manufacturing barrels.

In the United States, the situation is totally different. A lot of forests are still described as wild, meaning that strictly speaking they are not ‘grown’ or ‘managed’.

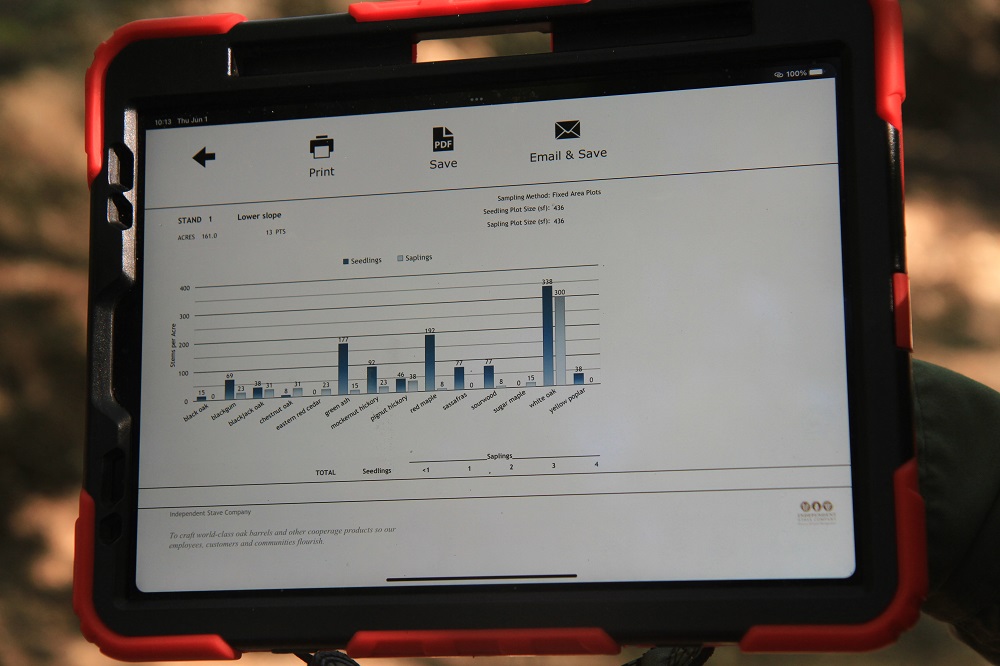

In the western part of the country, 75% of forest acreage is owned by the American government through National Forests, versus 5% in the East. Private owners simply cut the most worthwhile logs for clearance purposes every 20 years, but do not really manage the stands. Intervening between felling, however, increases the density of the white oak per hectare, avoids the spread of very competitive species like red maple and limits wildfires. Jeffrey Lewis, a forestry agent who works closely with ISC, explains that in non-managed forests, white oak covers between 20 and 25% of the forestry area, compared with 40 to 45% in managed forests. Based on this observation, the American government funds support programmes managed by universities in the different States, but also by independent groups such as ISC.

Lewis also explains that until recently, there was no real training programme for future foresters. Education on how to manage forests sustainably, both from an environmental and financial perspective, was difficult for owners to access. Often, they are not aware of the issues involved in forestry. Forests are only viewed as a financial investment with a return on the sale and purchase of the land itself; no profits are expected from using the forests.

The ISC group decided to address the issue by offering its expertise to forestry owners. In conjunction with universities, a team specialising in agro forestry is on hand to provide them with support and educate them about responsible management of their forests. The aim is to increase their yield of usable oak, and also to reduce the number of invasive species and the risk of fires, and to maintain the overall health of the forests. The model, designed as a win-win partnership, is considered by Jeffrey Lewis as a way of guaranteeing the long-term future of the industry. Although there should be no lack of oak in the medium or long term, he is concerned about the way the forests are managed. He also mentions the difficulties involving in finding labour for felling the trees – after decades of discrediting so-called manual work, which applies to the United States and other countries, there are only a few lumberjacks left.

It is estimated that white oak covers 30 million acres of forest land in the United States.

“It is estimated that white oak covers 30 million acres of forest land in the United States.”

American oak, a species used for spirits

One ring of growth reflects the development of a tree over one year and the size of the grain matches the width of the growth rings. Soil conditions (the richness of the soil), but also the weather (annual rainfall and temperatures), forestry techniques (for example dense or open stands, purpose of the clearances) and adverse climate events are all factors that have a decisive effect on the width of the rings. The faster the tree grows, the wider the rings and the coarser the grain. Stave mill operators classify logs, not based on the species they come from, but on the size of the grain in order to create the most consistent batches possible; contrary to common beliefs, the size of the grain is not really a characteristic of the species. American oak contains less tannin than French oak. Its benefits lie in its aromatic contribution during the maturation process through the break-down of its components by the various toasts.

“American oak contains less tannin than French oak. Its benefits lie in its aromatic contribution during the maturation process through the break-down of its components by the various toasts.”