The World of Baijiu: Aroma Classification, Its Historical Origins and Contemporary Relevance

Baijiu is a challenging spirit to define. It employs production methods and ingredients seldom found in its Western counterparts. It favors aromas and tastes not commonly found outside of Eastern culinary traditions. Making matters worse for the baijiu novice, it is not a single spirit but a family of diverse spirits.

That said, all baijius share a few common features. All baijiu is distilled from grain. All of these grains are fermented and distilled in a solid or semi-solid state using naturally harvested microorganic cultures called qu. Moreover, all baijiu is aged in a neutral vessel and blended to achieve balance and complexity.

Beyond these similarities, baijius can vary greatly in terms of production methods and flavor. At present the Chinese government recognizes twelve spirits in the category, and within those are several more sub-categories. These spirits are labelled according to their aroma, the traditional metric for assessing a drink’s quality in China—to compliment a baijiu in China, one typically says, “Hen xiang!” or “How aromatic!” The classification appears to use different considerations when naming different styles, such as intensity (“light aroma” and “strong aroma”), ingredients (“rice aroma”), or descriptors (“sauce aroma” and “sesame aroma”).

Baijius can vary greatly in terms of production methods and flavor. At present the Chinese government recognizes twelve spirits in the category, and within those are several more sub-categories.

The explanation for this classification system owes largely to baijiu’s long, fragmented history. The first conclusive evidence of spirits being distilled in China indicates that spirits arrived no later than eight hundred years ago, though were likely a variant of Middle Eastern arrack. Over the next several centuries a number of distinct spirits appeared in China, whose production methods and ingredients were largely determined by geographic region. These were the ancestors of the drink we now call baijiu. No formal attempt at comparative study of baijiu was made at the time, and no technical manuals or drawings of baijiu survive from this period.

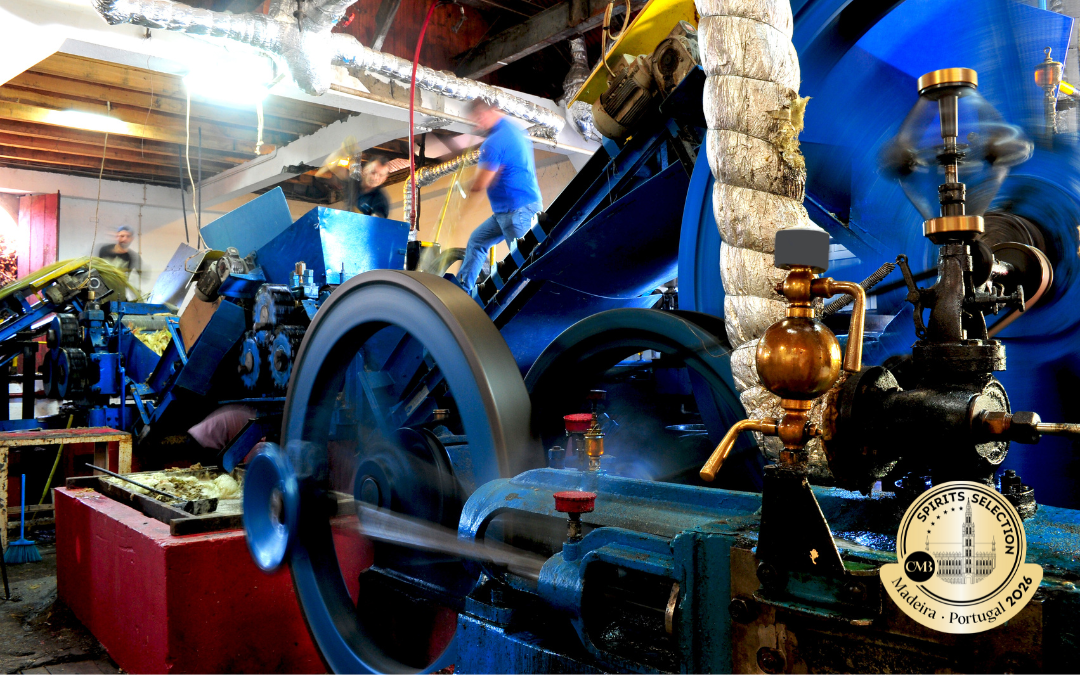

Fenjiu Cellar – Fenyang, Shanxi Province – & Sorghum grain plant

It was not until the 1950s, in the newly reformed People’s Republic of China, that the baijiu industry was fully modernized and properly studied. The government held its first wine and spirits evaluation in 1952, naming four regional baijiu distilleries the “Big Four”: Guizhou’s Kweichow Moutai, Sichuan’s Luzhou Laojiao, Shaanxi’s Xifengjiu and Shanxi’s Xinghuacun Fenjiu. These distilleries became stand-ins for their respective types in the earliest classification system, which listed four styles: Mao aroma, Lu aroma, Feng aroma and Fen aroma.

By the fifth and final national evaluation in 1979, the list of famous baijius had grown so large that it was decided to evaluate the samples according to their respective styles. Since the original classification system showed obvious favoritism to specific producers, and excluded large portions of the market, like the rice-based spirits of China’s southeast, the new classification system used four more neutral categories: sauce aroma (replacing Moutai), strong aroma (replacing Luzhou), light aroma (replacing Fenjiu) and rice aroma.

Baijiu at a Chinese supermarket

Baijiu at a Chinese supermarket

The resulting classification system is confusing and unintuitive to someone new to the baijiu category. But it is no more complex a breakdown than one would expect when describing a collection of spirits that developed over centuries in a geographic region roughly the same size as continental Europe.

Feng, or phoenix, aroma referred to a more unusual regional production style used by only a handful of distilleries, that did not fit neatly into any of the four new categories, so it was appended to the new categorization scheme under its original name. Other minor styles—often hybrids or variations of the major four styles—have also been added, officially and unofficially, to the aroma classification scheme in the time since: chi(fat) aroma, fuyu(layered, intense) aroma, laobaigan(old white dry) style, medicine aroma, mixed aroma, sesame aroma, small qu light aroma and special aroma.

The resulting classification system is confusing and unintuitive to someone new to the baijiu category. But it is no more complex a breakdown than one would expect when describing a collection of spirits that developed over centuries in a geographic region roughly the same size as continental Europe.

Most international spirits competitions do not bother to break baijiu into its component categories,which in this writer’s view is a mistake roughly equivalent to judging grape brandies against calvados, or whiskies alongside vodkas. Much to its credit, Spirits Selection by Concours Mondial de Bruxelles (for which I have judged) is the first and, as far as I know, only international competition to attempt to evaluate baijiu according to its classification. Though it currently only uses three of the outmoded 1952 categories, its commitment to education is noteworthy.

Most international spirits competitions do not bother to break baijiu into its component categories…Spirits Selection by Concours Mondial de Bruxelles is the first and only international competition to attempt to evaluate baijiu according to its classification.

As for broader institutional buy-in from government bodies, the situation is even worse. The United States Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau fails to even recognize baijiu—the world’s biggest category of spirits—in its spirits classification system. Nor does baijiu achieve mention in its European equivalents.

So the wider world has a long way to go in terms of baijiu understanding, but there are ways to hasten the process. International bodies must recognize and agree upon a unified classification scheme for baijiu, and use common language in describing it. Adopting the Chinese system makes the most sense, as it already exists and is widely accepted among baijiu producers. Not all or even most spirits scholars should be conversant in all of the many baijiu sub-categories, but most people should know the four major categories—rice, light, strong and sauce. Combined theses four styles account for the overwhelming majority of the baijiu industry, and provide enough grounding for understanding and appreciating the minor sub-categories.

International bodies must recognize and agree upon a unified classification scheme for baijiu, and use common language in describing it. Adopting the Chinese system makes the most sense.

Whatever baijiu’s future, it is crucial to drive home the message that all baijius are not alike. One taste does not represent all of China, and understanding the nuance that exists among baijius, moreover, is essential to understanding the category.

Derek Sandhaus

Author of the book « The Essentiel Guide of chinese spirits ». Co-founder of Ming River Baijiu and editor of www.drinkbaijiu.com

Author of the book « The Essentiel Guide of chinese spirits ». Co-founder of Ming River Baijiu and editor of www.drinkbaijiu.com