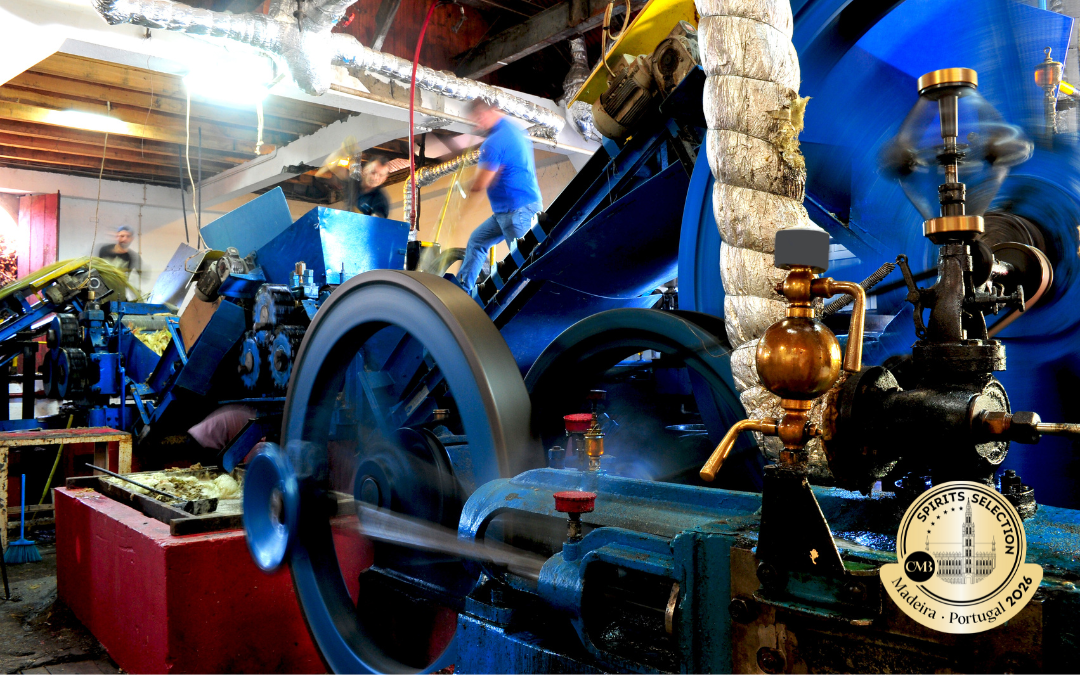

The crucial role of Saint-Pierre et Miquelon in the prohibition history

Thierry HEINS

Lockdown is a great time for reading and over the past few days I have delved into some books about Prohibition in the United States to get a better understanding of the part played by Saint Pierre and Miquelon in liquor smuggling. Spirits enthusiasts can discover the full story of this prosperous era for the archipelago through the two books referred to in this article. Enjoy!

It’s probably safe to say that most of you will not be able to locate France’s overseas territory Saint Pierre and Miquelon. Many people believe that this small island is situated in the West Indies or the Indian Ocean. In actual fact, it is located a few miles from Newfoundland, in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. Prior to Prohibition, Saint Pierre was a peaceful fishing village in the throes of a recession. The island was a home port for many boats sailing from St Malo or the Basque Country to fish cod from the shoals off Newfoundland during the season. It was dangerous, toilsome work and many sailors lost their lives in the process. Enactment of the Volstead Act in 1920 banned consumption of alcohol on United States soil, transforming life on the island and profoundly affecting the livelihoods of its inhabitants.

Bill McCoy discovers Saint Pierre

The Prohibition Act led to the emergence of myriad illegal stills in the United States. But the spirits they produced were of poor quality, and sometimes even lethal. Owners of ‘speakeasies’, restaurants and hotels soon began to look for alternative sources of imported spirits. Bill McCoy, a native of New York and resident of Florida, had a vested interest in transporting liquor. He acquired his first schooner, the ‘Henry L. Marshall’, to transport spirits between the Bahamas and Florida, to which Nassau customs officials turned a blind eye. At that time, Nassau charged $6 per case of spirits on all cargo entering the Bahamas. McCoy would then sail up the East coast of the United States to unload his shipments onto small motorboats that were waiting. He got richer by the day, buying a second boat which he renamed the Tomoka, but smuggling is a risky business. The ‘Marshall’ was seized by the U.S. Coast Guard, and McCoy was blacklisted by Canadian customs officials. The ‘Tomoka’ off the coast of Massachusetts was in need of repair work, and McCoy requested permission to sail to the port of Halifax in Canada. His request was met with a flat refusal. At that time, Nova Scotia was even more teetotal than the United States. McCoy was champing at the bit in a Halifax hotel, where he met a man with a French accent, Folquet. He was stunned to find out that Folquet was a native of a French colony so close to Canadian soil. The two became friendly and Folquet offered to send McCoy’s ship to Saint Pierre where it would be put in a dry dock for repairs. Folquet added that his shipping agency could take care of everything, but that it could also supply French spirits at competitive prices. Thus it was that the ‘Tomoka’ became the first smuggler ship to call at the island of Saint Pierre.

McCoy was stunned to find out that there was a French colony so close to Canadian soil.

Saint-Pierre – Photo Archipel

Saint-Pierre – Photo Archipel

Saint Pierre becomes a hub of liquor smuggling

Saint Pierre would soon supersede Nassau for alcohol trafficking, simply because its smuggling activities were conducted in a correct and orderly manner, with no violence. At the outset, however, there was a serious setback in developing trade in illegal alcohol. Most Americans had a penchant for rye whiskey, whisky and bourbon, none of which were produced in France. A 1919 decree issued by the French government prohibited its colonies from importing spirits of foreign origin; the post-war measure was designed to protect foreign currency. Merchants in Saint Pierre were frustrated by the decree and lobbied the government, so that in 1922 it was lifted. A minimal tax of around $0.4 was levied on each crate imported, far less than in Nassau, in order to fund local projects. Crates of liquor from places such as Scotland and Canada arrived in their shiploads, and for the first time in its history, the island balanced its budget. The golden age of Saint Pierre had begun.

All of the island’s residents switched to trading in spirits, and few continued to fish. They became longshoremen, warehouse staff and carriers, among others.

The stocks attracted hundreds of boats of smugglers, who came to get supplies of liquor then unload them at night on American shores, with the American Coast Guard relentlessly tracking them down. The schooners carried the goods to the American coast, staying in international waters whilst they waited for smaller, faster ships to come and collect the merchandise on board and offload it on the coast. The waters where the schooners waited became known as ‘Rum Row’.

Most Canadian distilleries opened sales offices on Saint Pierre and shipped stocks of Canadian whiskies there. Other agencies defended the interests of Scottish distilleries. Depots were built by Saint Pierre merchants and rented to Canadian distilleries so that they could store their products. The main distilleries, which established sales outlets in Saint Pierre, quickly cornered the market.

Above board

Between 1920 and 1933, residents of Saint Pierre would all benefit from this huge influx of currency and renewed business, at a time when the rest of the world was engulfed in a serious crisis and recession.

Life on Saint Pierre was more trouble-free and vapours from liquor replaced the smell of cod. The French State also cashed in, through its levies on each crate of liquor. The fact that bootleggers’ boats subsequently came to reload the goods to redistribute them along American coasts was of no concern to the French administration as there were no restrictions on trade.

Significant improvements were made to infrastructures on Saint Pierre, including the construction of more modern port facilities, renovation of all the island’s buildings and government blocks, building of roads and a drainage network.

Henri Morazé, the gentleman bootlegger

Whilst most people on Saint Pierre were happy to be used simply as postal addresses or act as intermediaries, ninety-five percent of the import business was in fact controlled by Canadian distilleries. The people of Saint Pierre pocketed a fairly moderate sum per litre, but they took no risks either.

Those who had to escape surveillance as they entered the United States after collecting supplies on Saint Pierre were the bootleggers. And obviously, the profits they amassed were commensurate with the risks they took.

Mouettes dans le port de Saint Pierre, face à l’île aux marins.

Mouettes dans le port de Saint Pierre, face à l’île aux marins.

22-year-old Saint Pierre native Henri Morazé came up with the idea of handling operations from start to finish. He decided to take to the seas, pick up supplies directly from France, Germany, Holland, the Bahamas and British Guiana and deliver them straight to his clients on the North American coast. As his business developed, he honed his techniques and equipped himself with radios and super-fast boats fitted with airplane engines – or speedboats – to thwart attempts by cutters, or American customs officers and their fast launches, to catch him.

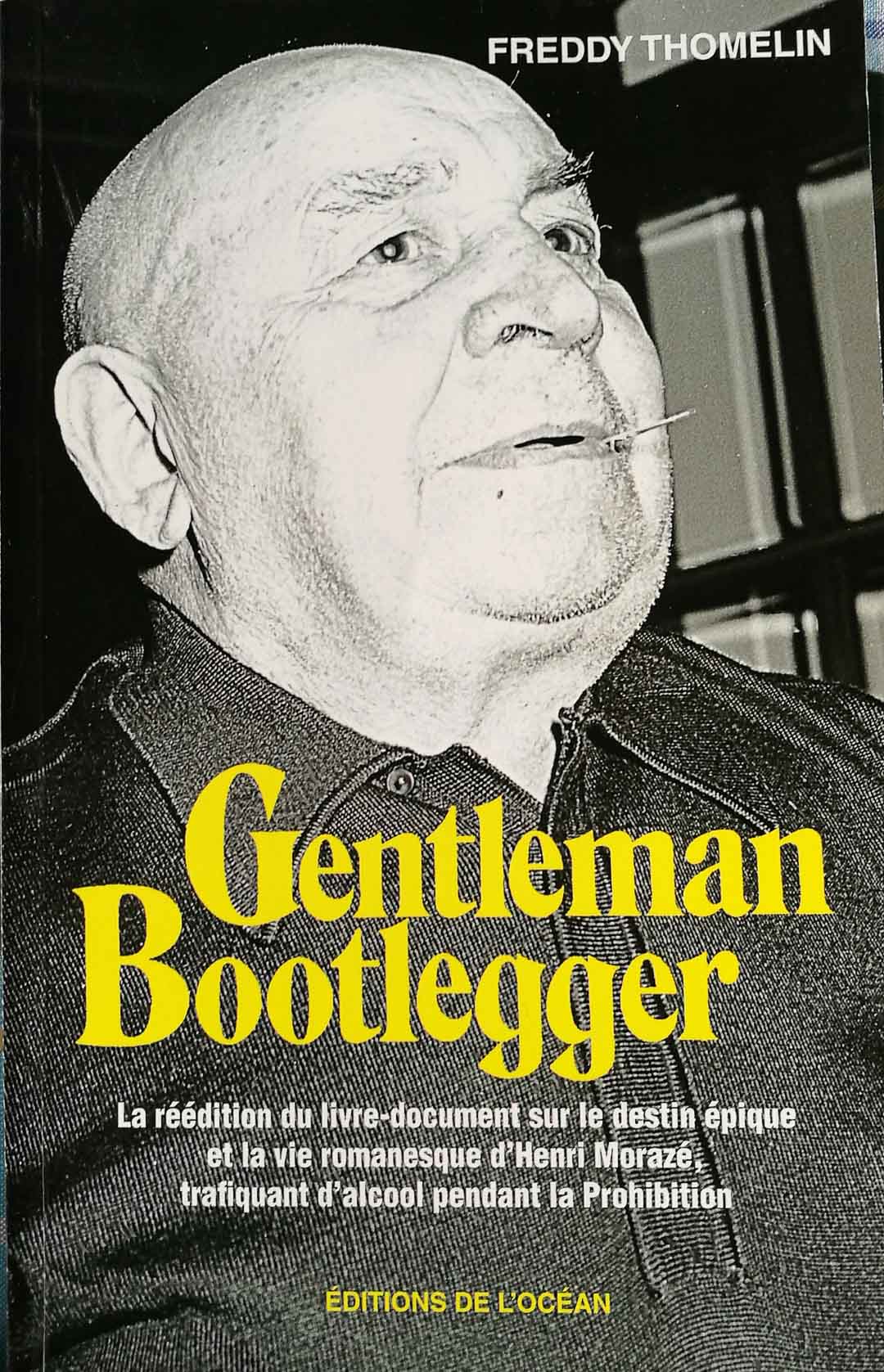

The epic tale and adventurous life of this ‘Gentleman Bootlegger’ is recounted in the book by journalist Freddy Thomelin, published in 1986 and re-released in 2017 by the Océan publishing house.

In the book, the author describes the adventures of Henri Morazé who, ironically, was not afraid of the cutters so much as the hijackers – organised gangs from the New York underworld who held ships to ransom. He preferred to deal with the toughest bootleggers rather than come face to face with the hijackers of Rum Row. He did dealings with Al Capone, whom he met in Chicago in 1926. Capone went to Saint Pierre himself. During his stay, Capone discussed the issue of wooden crates which were too noisy during transhipments, causing several ships to be intercepted by the U.S. Coast Guard. The solution came by pre-packing the bottles in jute bags, where each bottle had its own straw sleeve with handles sewn on to facilitate transhipment. The solution was soon introduced by all bootleggers.

He preferred to deal with the toughest bootleggers rather than come face to face with the hijackers of Rum Row. He did dealings with Al Capone.

Saint-Pierre – Photo « Des îles d’exception »

Saint-Pierre – Photo « Des îles d’exception »

The end of Prohibition, but not the end of smuggling

In 1933, the US Senate voted to abolish Prohibition. It was a promise made by newly-elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt who, during his campaign had stressed that Prohibition had in fact produced the opposite effect of what had been intended. People were drinking more alcohol than before, and the measure had allowed the Mafia to boom. In Saint Pierre, the news came as a bombshell.

The repeal of the Volstead Act did not spell the end of bootlegging in Saint Pierre, despite a significant scaling back of operations. Liquor produced in Canada was exported to Saint Pierre, only to be smuggled back to Canada and Newfoundland to avoid high customs and excise taxes in these territories. But things became more complicated. A year after the end of Prohibition, France gave in to pressure from the American government to stop delivering spirits from Saint Pierre. In 1935, companies shipping spirits from Saint Pierre were required to include a customs form with consignments, certifying that the products would be delivered to the destination stated on the customs clearance paperwork. Henri Morazé then changed tack, buying a boat in Europe that could ship 10,000 cases of alcohol – the ‘Greta Kure’. He would load his boat in Europe and anchor it just outside the territorial boundaries of Saint Pierre, in international waters. He would then send his super-fast smugglers’ ships to the mother ship, where they transhipped the goods and headed for the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. He subsequently bought back the enormous stocks of liquor in Saint Pierre, which had become unmarketable.

Subsequently, the United States offered lower customs duties on alcohol with countries willing to collaborate. France voted a decree to this effect in 1935, because lower trade tariffs with the United States were more advantageous than a few cases of liquor which, after all, were not bound for American soil but for Canada.

Smuggling with Canada continued until 1949. For Newfoundland, a 1987 annual report stated that smuggling spirits and cigarettes was a long-standing practice that continued to be both widespread and profitable. Smugglers from Newfoundland and Saint Pierre used small Saint Pierre boats called Doris or fishing boats to reach the Newfoundland coast, which is barely 20 km from Saint Pierre.

Henri Morazé amassed a considerable fortune, though never revealed exactly how much. An endearing figure admired by the people of Saint Pierre, he was elected Vice-Chairman of the Territorial Assembly in 1947. He ‘sobered down’ and focused on the island’s development, receiving the Legion of Honour in 1965.

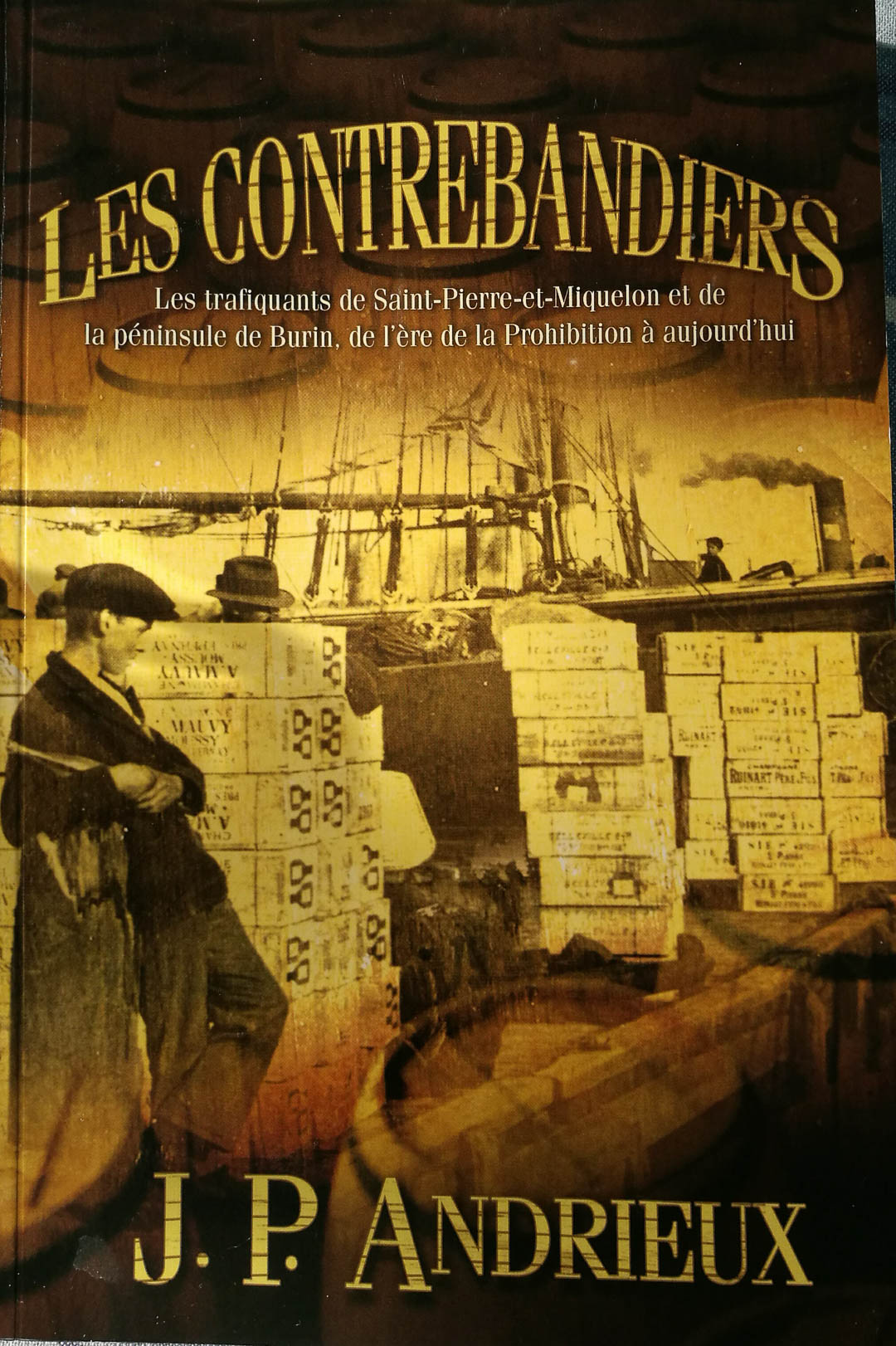

Les Contrebandiers – J.P. Andrieux – 2012 – Editions de l’Océan

Les Contrebandiers – J.P. Andrieux – 2012 – Editions de l’Océan

Gentleman Bootlegger – Freddy Thomelin – 2017 – Editions de l’Océan

Gentleman Bootlegger – Freddy Thomelin – 2017 – Editions de l’Océan